Day 2

The next morning we went back out to the streets, this time with our cameras. (My first Indian photographs!) We retraced our steps of the previous day circling the hotel to keep our bearings and came upon a group of people in a small square stringing flowers for wreaths. Very colorful, and it took a while to recognize the poverty that lay behind the beauty of the garments and the garlands, to realize these people probably slept right where they were working. The radius of their lives probably did not extend far beyond this small patch of urban subsistence.

There were shrines everywhere, some quite elaborate, others modest, almost hidden. It seems every other corner has one.

People were friendly, and we fell into easy conversations. No problem photographing. All this on the first day was positive.

I had heard from many sources that India would overwhelm the first-time visitor with its smells, the poverty, the chaos. But that has not happened to me; I have seen similar poverty in Africa, including the crippled beggars. Ditto for the smells and heat. I’m hardly indifferent to suffering, but India in that sense is not new to me. What is different is the scale, not the degree; there is more of everything here. India seems to be larger, more crowded.

Day 2 continued

Our plan was to get out of big city Bangalore as soon as possible and rest up from our journey in small town Mysore. The taxi from Bangalore took just over 3 hours – and it turned out to be a flirtation with death and destruction. We had a cowboy driver who kept the radio blaring and his foot on the gas, weaving in and out, passing into oncoming traffic, cutting all distances as close as possible. We were on the edge of our seats the entire trip, cringing. Traffic was bad enough; this driver increased the risk of serious accident exponentially. We felt lucky to arrive safely.

The hotel here (The Green Hotel) is quite pleasant, like an old English summer camp. It features a large garden and pleasant outdoor restaurant and a large building that was once a maharaja’s palace but which seems largely unused now. The bedrooms are in a low wing running along the garden and feature fans, plain beds and primitive bathrooms. But it is fine; I think we are relaxing as much from the drive as the plane flights.

Day 3

The morning after we arrived, we booked a car and driver to take us to a series of three temples which were quite remarkable. The first – Sravanabelagola - is a Jain temple on top of a mountain, and we had to climb 614 – count ‘em - stone steps to get to the top – barefoot except for socks (which we bought at the bottom). The place was full of pilgrims – including the two of us setting out on our own eccentric photographic pilgrimage. From the outset, we ran into a range of hawkers and hustlers but also people who just wanted to talk. “What country?” was the standard greeting. We talked to students, teachers and an engineer from San Jose who with his wife and two teenagers had recently returned to India to care for his elderly parents.

At the top of the mountain, we found a festival going on under the gaze of a huge 60 foot male nude statue (of Gomateshvara). What looked like a group of middle-age businessmen changed into white dhotis in order to worship. Some had their sons with them ‘on stage.’ Their wives and families were proudly photographing and videotaping them. It seemed to me more like a fraternity reunion than a truly serious worship; they were having far too good a time. There was music, washing and kissing of the statue’s feet (enormous toes the size of men). We took lots of photos; once again, no one seemed to mind. We intruded where we needed to intrude.

Day 3 Part 2

After we descended from Gomateshvara, we found our driver and took off to two other temples, these of the C11-13 Hoysala people. Both temples feature elaborate stone carvings. The first was Halebid, more linear than vertical with multiple friezes covering the exterior walls. The carvings are highly detailed with thousands of figures of deities, animals, rulers, mythical tales etc. The scale is vast, the figures intimate and repetitive. They were carved in blocks elsewhere (in some sort of primitive factory) and assembled on site. Why and by whom is still sketchy, I gather. More than I could really take in. I switched to black and white.

Day 3 Part 3

After Halebid, we went on to the next Hoysala temple of Belur where we found more of the same. Slightly smaller, more spread out, this temple too had friezes of thousands of figures. We could have benefited from guides at both places, but we contented ourselves with trying to make sense of what we saw by photographing. As usual, I was drawn more to the people than the monument; they stood out against the grey stone.

All in all, we were on the road for about 11 hours. We had a good driver this time - with the classic Hindustani Ambassador car - the roads were better, although not always paved, and the countryside very peaceful. The temperature has been quite mild, in the seventies I would guess, so we don’t need AC either in the car or in the room.

Kingfisher beers and dinner outdoors back at the hotel felt great – very relaxing. It’s amazing that on just our third day, we’re already in the swing of things, that instead of resting we’ve put in a full day photographing.

Day 4

Today (Sunday) we took a rickshaw (motor bike with rear seat) to see the town of Mysore. We were amazed to come upon yellow cows (dyed for some festival) wandering the streets. We went first to a market, just a field where women spread out their vegetables on cloths. Cows had free reign here too, stopping to nibble the goods until women shooed them away.

Then we took the rickshaw up to the temple on top of the hill overlooking the town. The top was crowded with school groups and throngs of pilgrims. We had to stand barefoot in a long line stretching around the temple in order to get in. Inside, the small spaces were jammed with people, but no one seems to get out of control, no pushing or shoving, no sense of claustrophobia. Photographing was difficult because of the crowds and the dim light.

When I went to retrieve my shoes, the guy in charge of the booth wanted to charge an exorbitant sum for the offerings he had thrust upon me when I had left our shoes. (I threw my offering away in order free my hands to photograph). Only when I threatened to call one of the police did he relent. (Earlier I had asked a mustachioed officer in military khaki for information about the lines into the temple. He gave me the information and then asked, “Is additional clarification required?” I said no, for the moment I had all the clarification I could use).

Afterward, we walked down past a large Nandi (Shiva’s bull). On the way down we met some young British kids who told us about their train ride the day before, the reverse of the one we were to take tomorrow to Madurai. We encountered our first monkeys near a shrine. We kept our respective distance. Our rickshaw driver met us at the bottom to take us back to the hotel. All in all, a good day; more photos. I’m comfortable now using the digital camera. I edit as I go along (although it’s hard to read the monitor in bright sunlight). Then I edit every night and download the cards onto my Epson storage viewer.

Day 5

Back into town again to see more of Mysore; another market, this time a ‘proper’ one with permanent stalls and a meat market designed to turn anyone into a vegetarian if you weren’t before. (Salvatore, already confirmed, passed on this part of the market).

Before checking out, I met one of the owners of the Green Hotel; it’s administered by some kind of trust set up by a descendent of the Maharajah who needed to find some use for the (white elephant) property. Profits go toward helping lower caste people – in particular working against child slavery and child sex rings - and all the employees are lower caste who they train and employ. So, it makes you feel good to support them.

Day 6

Through the hotel, we had booked a sleeper train to Madurai – ‘Second Class AC’ – was the designation. We left at 6 PM and arrived around 8 AM. The train was worn but clean enough, without anything you'd call frills. The tier of bunks was three high, two rows to a compartment. In an AC car, windows don’t open. Without AC, the windows are open and the coaches look crowded and stifling, like rolling tenements. Our condition was much better.

We were in with an Indian family of father, mother child (with a broken leg) and grandmother plus a single guy. Both Sal and I ended up in the top bunks; we had to climb a ladder of sorts to get up. We both had resolved not to eat – because we feared having to use the squat toilet as the train lurched along. A power bar, bananas and water sufficed and got me through the trip just fine. (I had left the bananas in the taxi at the station but was able to run after the taxi and retrieve them, thankfully).

The train had no announcements, the stations had no signs (that we could read, even in daylight), so we had to figure out when to get off by the approximate time of arrival. And, I found that the GPS on my cell phone told me the locations as went along. We were sleeping right next to the AC, and I think I got a head cold from it. The only other thing to mention about the train is the mice; quick dark darts under foot. Luckily we had been warned beforehand by the young Brits in Mysore who had done the train. I guess this being Hindu India, extermination is not an option; no hit-men here.

Booking the train was seamless, all arranged by the hotel over the phone or internet (I’m not sure which) with a printed ticket. The cost was quite cheap, just over $25 for both of us. Oddly, all that was required of us was our name and age. We saw the list of all the people and ages posted on the exterior of our train car. That’s how we found our seat; there was no conductor, although one did appear later to check our tickets.

Madurai was congested and not at all attractive; the hotel (Hotel Supreme which had been booked by our previous hotel) was on a typically crowded noisy and dusty city street; the lobby was dark and faintly ominous, our room plain and semi-functioning. But we both got hot showers (on different days). In general, we have been getting a shower every other day. After checking in, we had (non-veg) breakfast and then headed off on foot to see the temple - which is why we’re here.

We have discovered that hotels often have two entirely separate restaurants, one vegetarian, one non-veg. If you want eggs, never mind meat or fish, you have to go to the non-veg restaurants.

The temple in Madurai is quite remarkable. It has four enormous towers at the corners; within the compound are houses shrines, stables, shops, eating and sleeping facilities. These temples are really self-contained cities, and you can see how in the old days, all the life of a fort or temple went on within the walls. The variety of shrines seems endless; the most sacred don't allow non-Hindus to enter, but we had no problem photographing anything else. We spent several hours there and then took a break for lunch back at the hotel. Once again, we had to do the whole temple - acres ( 6 hectares, according to the guide book) - in our bare feet (no socks allowed this time) so after a while I was really hobbling. We had left our shoes in a shop and when retrieving them, fell into pleasant conversation with the young owner covering a gamut of history, religion, politics etc. We spent almost an hour there talking and ended up buying some jewelry (Sal) and pillow covers (me).

We also took a rickshaw to the Gandhi Museum which presented a very good history of India, the British in India, the Independence movement and Gandhi's role. (I knew much of this because I had just read Ved Mehta’s excellent biography of Gandhi; showing great confidence, he managed to write an insightful book despite over 400 prior biographies of Gandhi). We returned to the temple in the afternoon to walk some more, follow an elephant circling the temple and just sit and watch the people.

Dinner was on the rooftop restaurant of the hotel, nice and cool and breezy with a view of the city, temple towers in the mid distance. We continue to luck out with the weather on this trip.

Day 6 continued

We hired a driver from right in front of our hotel to take us from Madurai to our next destination, Tiruchirappalli (Trichy for short). The driver, Arun, turned out to be very good. I guess we were attracted to him initially as the opposite of the young fool we had from Bangalore to Mysore. Arun has been driving for 22 years and his car, a classic Hindustani Ambassador has been on the road for 20 years itself. It had no AC (which we don’t need anyhow) and reached about 45 miles an hour tops. We decided this was a good feature given the craziness of the Indian roads.

Indian roads are always full of activity, all sorts of vehicles dodging one another in a crazy ballet. No one seems to break the rules, although the rules of the road would be hard to codify. (I noticed numerous driving schools, but how do they teach this chaos?) We’ve gotten used to the driving here – although I would never want to drive here myself - and I’ve begun to catalogue some of the mannerisms of the Indian roads. To wit: Any vehicle coming from a side street can enter the larger street at will; it’s up to the drivers in the main street to react. Thus, no one entering hesitates or even needs to look. Also, rear view mirrors are superfluous – no one looks behind or would even think of it. (Many vehicles don’t have external rear view mirrors; they have been sheared off by other vehicles.) Spatial distances are different here; tailgating is the norm, and sometimes just prior to overtaking, the bumper of the car is literally under the truck ahead.

Some of the truck loads are huge and occupy most of the road, covering both lanes. I kept trying to photograph the loads and the congestion from the car.

Along the way, Arun was amenable to stopping whenever we saw a photo we wanted, so it was a slow trip, unrushed, the kind both Salvatore and I like, why we prefer being on our own instead of with an organized tour. We came across two remarkable roadside shrines along the way, the first in a small town where we stopped for coconut milk and the second shrine totally empty, almost abandoned. After a while, a caretaker and his wife came down from their hut to see what we were doing. A simple and humble couple, with Arun’s help they allowed us to photograph them.

Day 7

In Trichy, we went straight to the temple - another enormous self- contained Hindu city. We walked all through it - barefoot but with socks - for several hours. Once again, there were numerous shrines, some elephants and lots of people to photograph. At each shrine, something was going on, some form of worship, and I began to wonder how people pick the shrine where they worship. Do they have favorites? Or do they do them all in some sequence? I don’t know, but there was constant activity.

Then, as it began to get dark, we could sense that something was in the wind; people were lining up in expectation of something. We waited, and after a while an elephant with a beautiful robe was brought out. And sure enough, a procession began – with drums and high-pitched flutes, fire, singers, dancers, priests and acolytes. And us. Despite our sore feet, we followed the procession for about two hours, moving with them past throngs crowding the inner roads of the temple, past women prostrating themselves on the pavement. It was all sort of a blur. I should point out that all the steps of the temples are granite; the streets inside are like city streets, asphalt.

Surprisingly, we were accepted as part of the procession and guided along as we photographed. (Hardly anyone in India has protested our taking their photographs, and often we are begged to do so, sometimes for money but usually not). Despite the fervor of the religious worship on display, I was struck by what a good time people in the procession were having, laughing and joking as they - about 20 men - carried a huge palanquin mounted on top of long logs. They were sweating but enjoying themselves and even invited me to join them carrying. I declined, more interested in photographing than lifting. It was a great evening; we felt lucky to have stumbled on this. By the end, however, when we’d had enough and fell out of the procession, we had no idea of where we were, where we had left our shoes or where our driver was. We discovered we were at the opposite gate – the towers all look alike - and there were no motorbike rickshaws left inside. So we prevailed upon an old man with a bicycle rickshaw to take us to the other side of the temple where we were reunited with our shoes and driver.

In Trichy we had had trouble finding a room and ended up in a second tier place, our third choice. Trichy is a large commercial town, and evidently, there is a constant demand for rooms. For both breakfast and dinner, we went to the best hotel in town - where we hadn’t been able to get a room. The food was acceptable. Because we came in off the street, our hotel made us put down a security deposit (refunded at checkout); that and registration necessitated multiple entries and signatures in three big ledger books. There is a record-keeping mania here; for every transaction there must be a receipt. I can see why Indians have adapted to computers so readily.

We also spent some time in town, and while photographing a small (Christian) shrine, school let out, and we were besieged with kids wanting pictures and pens. (If I had it to do over again, I would buy large numbers of bic pens, because every kid wants one; we get asked all the time.)

Day 8

After Trichy we pushed on to Thanjavur. Tanjore is the old name; many cities in India have both old (English) and new (post-Independence) names - so you say Bangalore and I say Bengaluru, you say Varanasi and I say Benares, you say Madras and I say Chennai and so on. Tanjore was the site of another renowned temple, but after the previous night, I'd had enough of temples and just waited in the shade of the entrance while Sal went in and around to photograph. So, I have no photographs of Tanjore.

Given our problems in Trichy with finding a hotel, we decided to stay in Tanjore and ended up in a very good hotel (Hotel Gananam) the best so far. At one point, I decided to look for more cough drops to fight my lingering cold (from the train) and was directed to a pharmacy around the corner from our hotel. It was late at night, but the pharmacy, open to the street, was doing a booming business. I counted at least a dozen employees behind the counter and in the stacks above where the drugs were stored. One guy with a laptop entered all the orders fed to him by a bevy of clerks and generated the receipts. Another, next to him, manned the single cash register. There was no line; customers waved their prescriptions and called out to be waited on. Nor was there any discernable order to all the activity behind the counter. Yet, it all seemed to work; I was waited on without too much waiting, and lo and behold a receipt ended up in my hands, then the pills, all for about a buck. Once again, despite the shouting, there was no shoving or displays of temper; Indians seem pretty placid, certainly friendly to outsiders.We negotiated with Arun to take us all the way from Tanjore to Cochin, a two day trip. Considering there were few good East-West options in Southern India whether traveling by train or bus, we decided to stick with Arun. We were comfortable with him; he was a good driver, spoke pretty good English and was amenable to our frequent stops. But it turned into a long, slow trip. The temperature got hotter the further West we went, but it was a long way from stifling. Even without AC we were o.k. for most of the trip.

We might have made it in one day had we pressed. Instead, we agreed to go to Cochin via Munnar where we would spend the night. The benefit of driving slowly was that we were able to stop and photograph when we wanted; And, we found another remarkable shrine along the road with statues of all sorts and priests in attendance. Several women were gathered outside to receive offerings of food. It seemed sort of a welfare line, but I couldn't be certain if these women were in need of food per se or of a spiritual offering. So often in India, poverty is masked by color; even street sweepers wear bright saris.

Day 9

Munnar is a mountain tea and coffee growing area in what are called the Western Ghats (steps). What we hadn’t realized (because we hadn’t been told) was that since Arun’s car didn’t have an all-India permit, he had arranged for his ‘brother’ to take us into Munnar and then to Cochin. So, on a street corner in a nondescript town at the foot of the mountain, we said goodbye to Arun and switched Ambassadors. He bought us all cold drinks at a corner stand by way of celebration to mark the end of what had been a pleasant journey together. Our new driver hardly spoke any English – “English small,” he kept telling us, as if we couldn’t figure that out. But he was being apologetic.

Planted by the British, the Munnar plantations are now run by one of the top industrialists in India, Rattan Tata. As we climbed up the Eastern (coffee) side of the mountain, beautiful landscapes changed with each switchback of the steep road. It reminded me of Route One along the California coast but without the water. Lots of rock slides and evidence of work in progress to fix them. But not much actual work going on. It’s hard to see how they’ll finish all they’ve started before the next rains. (India is a permanently unfinished country, always works in progress).

Whereas on the eastern side, they grew coffee, on the western side they grow tea, and that is where the town of Munnar is located. We had trouble finding a room in Munnar – all bad or booked - but we ended up in a guest house with a very sweet Pentecostal family. There are lots of Christians in this part of India, Catholics and Pentecostals primarily. So, you see Christian churches and shrines mixed in with Hindu temples and Moslem mosques. Very interesting. We hear of troubles between religions in India. But in Munnar, if they don’t interact, they seem at least to coexist.

The tea plantations are really remarkable; they are comprised of thousands of bushes planted not in rows but in irregular patterns. We saw some women picking in the morning as we left. They pick only the small bright green new leaves, and it seems the plants produce these all year long – or at least not at one time of year only. Workers are employed year round and are given company housing (long rows of adjoining rooms) with free rent and utilities. We were told they were well paid by Indian standards. Therefore they are happy. (I’m always skeptical of good news like this). All the plantations in and around Munnar are owned by Tata, one of India's leading industrialists. Tata everything; tea, trucks, jeeps, cars and who knows what else. (While we were in India, the ranking of the world’s ten richest men came out. Four of the top ten were Indian – but not Tata, which, given the ubiquity of his name, I found surprising.)

It was cool here in the mountains, and we needed sweaters. For dinner, we were directed to a restaurant near our guest house, and it turned out to be a strange place, all long communal tables, no beer, awful service and mediocre food to boot. We wondered if the no beer status was because of religion or indifference – but whatever, the unsatisfying food, service and atmosphere could have benefited from a good large Kingfisher. Our first night without one.

Days 10 - 13

Driving into Cochin, it looked pretty awful, crowded and industrial. On (toll) bridges we crossed lagoons flanked by high rise apartments, thinking that was where we must be headed, sort of a poor man’s Miami beach. But then we descended into more heavy urban traffic only to emerge - finally - into this quiet corner of India - Fort Cochin as opposed to Cochin itself. The hotel (Ann’s Residency) is very comfortable with an excellent breakfast served in a nice open air restaurant. (The hotel was recommended by a group of four American women staying at the Green Hotel in Mysore, verified by the Lonely Planet Guide).

As soon as we began walking around Ft. Cochin, we could see it was a major tourist destination. We hadn’t been accustomed to this elsewhere; in other cities, we were used to seeing a handful of foreign tourists sprinkled in amongst the Indians, but this was very different. It’s easy to see why Ft. Cochin so popular with foreigners; it’s quiet, peaceful, not too hot and on the water. Pretty clean, too – except for the water. And there are plenty of good restaurants, all featuring ocean-caught seafood; one night we blew a hundred bucks on grilled fish, jumbo prawns etc. in a fancy restaurant set in an old colonial building overlooking the water. Dining with the ‘other half.’

Here the restaurants aren't 'segregated.' Prior, when we were in the East, most hotels practiced culinary apartheid – with separate vegetarian and non-vegetarian restaurants, separate and distinct kitchens. We tend to favor the non-veg - because there we can get things such as eggs and fish - not so in the strictly veggie restaurants. Here, all things blend, the menus have both vegetarian and non-vegetarian sections, plus some Chinese and a European style breakfast. But the clientele wherever we ate in Ft. Cochin was 99% white.

The Portuguese came here looking for spices. (Vasco de Gama was buried here originally). Thus, there remains a large Catholic influence. We spent hours Sunday at a large cathedral jammed- packed with worshipers. We had to wait for the service to end so we could photograph the colorfully dressed women emerging. The service seemed interminable, but finally we were rewarded; processions encircled the church several times - these people did not want to leave – and we were able to get the photographs we wanted (at least the opportunity). Rounds of firecrackers were set off as well.

Then, we heard about a Hindu festival and procession with elephants, so after dinner we set out to find it, guided to it by the noise. It turned out to have dancers, musicians, elephants and long lines of young girls holding food offerings and candles. It seemed like some medieval lining up of all the virgins in the kingdom. Once again, we had free reign to photograph amidst the girls and the procession. People were very accommodating.

The next day we came upon a Jain temple at pigeon feeding time. Swarms of birds descended to eat grain out of the hands of the faithful. Afterward, a man told us he had been doing this every day for 18 years as an act of devotion. Jains do not believe in harming any living creature; here that has turned into a form of pigeon worship.

There is also a section of Ft. Cochin called Jew Town with an old synagogue at the end of a small street lined with shops. One of those shops was a bookstore, so while Sal went into the synagogue to look around, I chose to remain in my spiritual home, the bookstore (Incy Bella), looking through a very good selection of photo books on India. (The synagogue prohibited photographs, anyhow.) Only 13 Jews remain in Ft. Cochin.

The color of India is in the women – in the saris. The men seem almost invisible by comparison, while the women, rich or poor, are like birds of paradise. They enliven the landscape, and I follow them around, drawn to the colors like bees to flowers. Pollination, anyone?

We have been in Ft. Cochin four days and there have been two strikes. The first was for transport only, but we could still find rickshaws operating. Today it is a general strike with nothing moving – and no way to get to the airport as we had planned. So we arranged to stay another day but had to spend one night at another hotel, sort of an annex to Ann’s Residency. It was plainer and with mosquitoes but no nets. (Ft. Cochin is the first place on the trip where we have had to use AC and mosquito nets.)

We walked along the shore promenade and photographed the old Dutch cemetery – they were here too. Pausing for a coconut drink under the shade of one of the large trees, we fell into conversation about Indian religion and politics with a young guy on a motor bike. Luckily we can walk from the hotel to the waterfront where they bring in the fish and where the Chinese fishing nets operate. (The Chinese were here too.) These are remarkable contraptions with large square nets that are dropped into the water from shore by a series of ropes and rocks to weight the boom. Normally they are left in the water for hours, but for the tourists, they operate continually, pulling up almost nothing every five minutes. But it’s a good show.

Today at our hotel a group of Brits arrived, all on old style Enfield motor bikes, big, black beasts with no windscreens or frills, nandis on wheels. They are doing a week tour of Southern India by bike. Given the traffic, we thought they had to be crazy, but all said they had no problems and all was fine. Then, on the street I ran into a young Canadian girl who told me she and her boyfriend had been traveling throughout Southern India on their Enfield – all alone. They had come all the way from Calcutta. Now, that’s really nuts! She said she was exhausted because couldn’t relax for a second, even though she wasn’t doing any of the driving.

We keep running into more Hindu festivals - one last night started outside our hotel in daylight, so we spent some time photographing three elephants, their handlers and musicians who warmed up for well over an hour, very hypnotic.

Because of the strike, we had to stay an extra day – not a bad place to be stuck - so we leave tomorrow after four nights here, flying via Mumbai to Aurangabad to visit the Ajanta and Ellora caves. We plan to leave there on another night train to Varanasi, arriving Feb 24. Booked by the hotel here in Ft. Cochin. That's our plan so far.

Days 14 - 16

We reached Aurangabad by plane, two easy flights that only took a couple of hours to transport us to an entirely different landscape. We passed through Bombay but thankfully didn't have to leave the airport and deal with that vast city. Aurangabad is the gateway to the famous caves of Ellora and Ajanta, which is why we are here.

Here in the north, it feels as if the color has been sucked out of India like a dried orange. This is near-desert, dusty and brown. The temperature here is cooler and much drier, so even in the heat of the day, the sun is bearable.

Going in and out of these caves requires a lot of walking in direct sun, but the caves themselves are quite cool and offer respite from the heat. The caves at Ajanta are Buddhist; at Ellora they are Hindu, Buddhist and Jain. I must say I can’t tell the difference. The carvings and paintings at Ajanta are not in great condition, and restoration has been fitful at best. These caves lay idle for years, decades, centuries, - who knows? - until an Englishman hunting a tiger in 1890 literally stumbled on them. It’s hard to imagine they were abandoned or ignored (probably not by the locals) but they are cut into hillsides, and evidently the vegetation just grew over the entrances. They are remarkable for the industry required to make them. Like the pyramids, it’s hard to imagine how and for what purpose they were created. Both Ajanta and Ellora were carved out of mountain sides – using mass labor for sure. Photographically, the caves are not so exciting. When I’m photographing, I’m less interested in the history of a place than I am in the forms and activity. It’s through the photography that I become interested in the culture; I do my reading after the fact. Drawn to color, I found myself photographing the people visiting the caves, including large groups of school children. There are around 30 caves in each locale, side by side in a great horseshoe arc facing a stream below. Why so many so similar? I don’t know. Probably because each generation – or ruler- felt the need to express its / his devotion.

Near Ellora dominating a high mountain is the C11 fort of Daulatabad. Even though neither of us wanted to climb the mountain, we decided to stop and look around. The entrance is through a series of large gates. Inside we found stone workers building a wall, chiseling huge stones by hand and carrying them up to the wall with what looked like a stretcher. It was like lurching back in time several centuries. All construction is done by mass labor rather than machine; we have not seen a single crane or concrete mixer on our entire trip (except near the Delhi airport). Contrast this with China where scores of cranes dot every city landscape.

This is a Moslem community and at one point we were surrounded by high school boys and girls, all flowing through the arches and gates wanting to have their picture taken.

One afternoon, we directed our driver to take us to what is termed the mini-Taj, another mausoleum with the same general design as the Taj Mahal but without the inlay and fine detail. It’s called Bibi-ka-Maqbara and was built for the empress of Aurangzeb by his son, the grandson of Shah Jahan who built the Taj, in sort of a filial emulation. It was quiet and contemplative and very beautiful. The scale is intimate. Families were posing for photos and walking along the elongated reflecting pond. At one point, I encountered a group of Moslem teen-age girls, all covered in black, laughing and giggling (like any teen-age girls) making jokes (I thought) about my shorts. So I asked them if I could take their picture, and the others pushed one out for me to photograph, then went on down the path laughing and joking.

We found ourselves stuck again, this time due to poor planning and this time in a dreary hotel in Aurangabad, We had to stay here an extra day because we miscalculated how much time we would need to see the caves. Then, when we tried to change our ticket, we found the Friday night train was full. So, here we are in a dump of a hotel - the only room in town due to an enormous wedding party that has filled up every good hotel. Every morning the clerk promises us a better room, and every evening, he says unfortunately, nobody has checked out, so he can’t move us.

Today we stopped by the hotel where the wedding was held to see some of the trimmings - amazing and elaborate, with flower petals arranged in the lobby floor and all the hallways, whole pavilions built around the lush garden etc. Two Indias! Trying to change our train tickets yesterday was enlightening. We didn't trust the hotel people's English to understand what we wanted, so we went to the station ourselves and stood in a long hot line (the express!) for about 40 minutes. In modern India, all train and plane bookings can be done in a flash over the phone or internet. But if you don't have that access, then you live in a very different India. We got a small glimpse of it at the station.

There is extreme poverty here, and the extent, if not the degree, is surprising to me. At the same, time, India is booming. It can feed itself - we passed fertile fields of cotton, wheat, rice and plenty of veggies – which is a remarkable achievement, given the not so distant past. And, there are pieces of high tech that glisten like jewels against the dust and dirt and dullness of the cities. But it seems that the progress only casts the poverty in deeper shadow. The gap between the extremes is widening.

In the end, after all the waiting in line, we found that all the seats were booked on the (Friday) train we wanted. So, we had to stay another day; we used that time to re-visit Ellora so Sal could get some more/better photographs. I waited for him while he went in, sitting on a bench reading. Remarkably, I was left alone; it was the first half hour since being in India in which no one tried to speak to me.

Afterward, we stopped at Khuldabad, where the body of Aurangzeb, the last great Mughal Emperor, is buried. (What a tyrant he was! And what a comedown, from Mughal emperor to this dusty backwater). Khuldabad is a Moslem enclave, and both mosques we saw there turned out to be fascinating, charming in their simplicity and quietude. (Much more interesting than the caves). Sal gave a young blind man rupees for two dollars that he couldn’t use; other beggars pestered us for money, and we gave donations liberally to all the shrines inside. The guides were good. And, we could photograph at will, which is what we appreciate most of all.

All this served to remind us of the fact that in India, Moslems, Hindus and Christians all live side by side in relative peace if not in harmony and seem to respect each others’ customs. Then throw in Buddhists, Jains and Pentecostals and it gets even more interesting. I think there is no such thing as secular India.

The other thing of interest is that to date we have seen almost no police, not on the roads, not in the towns, only in government buildings and large public places. Indians seem able to regulate themselves without too much direction or (external) control by the state. Elections are coming up and although we don't know much about them, candidates billboards - mostly portraits of candidate slates - are everywhere. There is also a plethora of daily newspapers.

On our last night here, we went out to one of the best hotels in town (where we couldn’t get a room) to have a good all-you-can-eat buffet dinner. It’s a very elegant setting, and we plan to return tomorrow for lunch on our way to Jalgon for the train.

Day 17

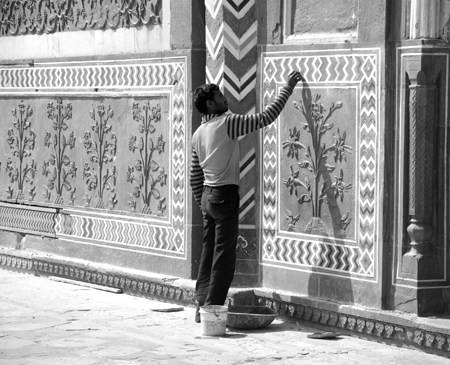

We have our driver used to our stopping along the road when we see something we want to photograph – today a Hanuman shrine on top of a small hill set back off the road. We climbed up to find a man covering the large statue with the characteristic bright orange paste. Sal negotiated with the priest for some pot but came up empty. Then, we came upon another shrine, this one with beautifully painted walls that caught our eye. When we stopped, we found we were in a small village with a flock of school children who all came out to greet us. They were excited yet reserved, watching our every move as we photographed them. It’s a trade-off of sorts; we take away photographs, they take away a memory of two strange men. I’m not sure which lasts longer or fades first.

En route to Jalgon to catch the train for Varanasi, we had our first accident. I had been saying I hope we hit something small instead of being hit by something big. But then, we were hit by something small, two guys on a motor bike who failed to stop in time. I couldn't see behind us, but Sal said they were up and walking and not too badly hurt. So after exchanging a few shouts and oaths, we took off leaving them in the dust. That's how its done here, I guess.

Although it’s a small town, the Jalgon train station was filled with thousands of people; the prospect of getting information about our train was nil. But I had read that the owner of a hotel nearby was helpful, and sure enough he lived up to his reputation. First, by phone he confirmed our seats - we had thought we were already confirmed, but now we learned we were only waitlisted. Then, he told us which track we were on and where to find the station master. We did, and the stationmaster told us where on the platform our car would stop. But the train was late and other trains came in before ours. In the meantime, darkness fell. No one on the platform spoke much English; we would ask “is this the train to Varanasi”? And some would say yes and some would say no and some would just giggle.

In the dark it was hard to read any signs on the trains. There are no people to assist you on the platform, and no conductors on the train to help you board. The train we thought was ours came in - but we couldn't be sure. We couldn't see our carriage number. So, I ran back to the station master - almost the whole length of the long platform frantically asking him if this was our train. IT WAS! He took off with me, both of us running back along the platform at top speed to find Sal, grab our bags and try to get on board. By this time the train was pulling out. As our carriage slowly passed us, he threw Sal's bags onto the train. Sal ran to get on board. But he slipped - and this picture will stay with me for a long time - between the moving train and the platform, hanging on for dear life as people on the train grabbed him and pulled him up and in. I was next. I thought I wasn’t going to make it. The train was picking up speed. But the station master threw my bags on, and I too ran to board, grabbing the vertical bar on both sides of the door and pulled into the train by other passengers. We were on the train and on our way! Sal's knee was bloody and his entire right thigh scraped by the side of the train I guess. So the first thing we did was some quick first aid, giving thanks that somehow he had escaped a really serious accident.

As was the case on our previous train trip, we were the only non-Indians in sight. Oddly, on this trip no one spoke to us; normally we can't go two feet without somebody approaching us to talk. The other big surprise was finding out how long the trip was - 20 hours. We hadn't known that prior. So we started out around 7:30 PM (about 30 minutes late) and arrived here at 3PM. As is our strategy in order to avoid using the bathrooms, we don't eat on the train except bananas and oranges that we bring with us. Even on this long trip, it's worked. We keep saying, ‘thank God for bananas and water;’ without them, we couldn’t make it in India. Whether we go to Agra by train is still undecided. I think we'd prefer another mode of transportation.

Days 18 and 19

When I first thought of going to India, I thought a long period of time, a minimum of 5 weeks, would be necessary to absorb the spirit (spirituality) of the country, to let India sink in so to speak. But it hasn't worked out that way; we've been constantly on the move, covering a lot of ground and not staying too long in any one place, trying to see as much as we can. At this point, I'm not convinced that India is a spiritual country - religious for sure, more than any other country I've ever seen. But spiritual? Maybe in some remote areas or in the Ashrams. But even with the Ashram, you emerge into chaos. And the Sadus who wander around half naked and profess to be otherworldly still exist in the midst of the turmoil and disorder that is India. They don’t seem to me to have escaped this world. Varanasi brings these thoughts to a boil.

We arrived in Varanasi late afternoon and immediately began negotiations outside the train station to get to our hotel (the Rashmi Guest House / Palace on the River). We learned that motorized vehicles were not allowed to go into that part of town, close to the river. So, after much haggling and discussion we got into a motor rickshaw and were dropped off on a busy street corner. That was the abrupt end of the ride, and we had no idea where we were. After 10 or 15 minutes of wondering and waiting, we were collected by hotel porters sent to fetch us. We entered a shit-laden alley so narrow and crowded that the porters could not carry our bags by hand; they had to put them on their heads in order to get through. But once we reached the hotel which was right on the river, we no longer had to deal with the chaos of the town, only the chaos of the river and the ghats that line it. It’s a separate world, what we had come to see. The hotel was fine; because of a booking mix up, instead of the double room we had requested, we negotiated two separate rooms at the reduced rate of $42 each. We ate all our meals – breakfast, lunch and dinner - on the rooftop restaurant of the hotel which overlooked the broad panorama of the river. That way we could concentrate on photography and not worry about anything else.

Our first venture out along the ghats brought us to the funeral pyres on the river bank where some 200 bodies are burned every day of the year. The cremation is a very ritualized process, and we were able to witness most of what goes on. Oddly, despite the rituals, there didn't seem to be much ceremony, nothing like a Western funeral or mourning, no gathering of family and friends etc. It was hard to pick out the relatives. For the Hindus, the Ganges is sacred, and this is the gateway to paradise. For me, it was a grim reminder of my own mortality. Visiting Varanasi may be better for younger people who aren’t as readily prompted to envision their own demise. And for a non-believer, it’s hard to visualize paradise in the smoky pyres and foul river. We didn't linger.

We could see that the river was very low by the number of steps leading down to the water and by the high water marks which were visible some 60 or 70 feet above the present water level. The other side of the river merges into a low lying plain rather than a steep embankment like the one we are on. At present, there is a sand bar on the other side. In the rainy season, it would be totally submerged. Given the breadth of the river and the height of the water marks at the top of the ghats, the Monsoon rains must carry an unbelievable amount of water. (The book “Chasing the Monsoon” which Salvatore lent me vividly portrays the rich culture of the Monsoon rains and the incredible power of the water.)

I preferred to concentrate on the women bathing in the Ganges. Having looked at so many photographs of Varanasi and the Ganges, I was anxious to see for myself. It is a brilliantly colorful sight along the ghats, full of activity and a constantly changing palette of bright colors. We had no problems taking photos. I walked back and forth several times photographing women preparing with oils and flowers, women at the water’s edge (with morning light reflecting off the river) women fully immersing themselves, drying afterwards etc. I observed great reverence but also great happiness; everyone seemed to be in a good mood. Although all are engaged in the same ritual, they do it individually, creating endless motion and great variety. A great show, and all I had hoped for, interesting choreography and a riot of color. This is one place that the disorder of Indian life is a plus – at least for the photographer.

We took a boat across the river to the other side where families were also bathing in the river. The shore was just a sand bank seasonally visible during the current low water level. It was much more relaxed and less crowded than the ghats. Once again, I was struck by how good a time people were having in the river. Looking across the Ganges gave us a panorama of Varansi, the ghats and buildings spread along the river. On our return, we took the boat (one man rowing and poling) up and down the river along the ghats so as to get a view of all the activity from the water.

Day 20

We did return to the pyres in order to photograph. It is forbidden to photograph the cremations - which in India means you have to pay someone. The prices were outrageous and very limiting - something like $100 per photo. We negotiated for over an hour with a young ‘guide’ who said he was an official representative of the hospice that accommodated people waiting to die and organized the cremations. For all I know, he was a self-appointed hustler, but there was no way to shake him. I saw similar negotiations going between other tourists and ‘guides’ but wasn’t able to compare prices.

In the end we got 5 photos for that price. But first, we had to go up a pitch black stairway in the hospice to hand over our wads of money to an old crone sitting on the floor so that our payment was in the form of a donation to the hospice rather than a bribe. (What a bag lady!) It all seemed suspect, and we were upset at having to pay so much to photograph so little. Even worse, every time we raised the camera, our guide and his assistants assigned to watch us would say "one photo" and we had to convince him we were just looking or framing and hadn’t snapped the shutter. Pretty intolerable. It took well over an hour to get our 5 photos – normally we would have taken a couple rolls in that time – and I was happy to get out of there. It felt ghoulish photographing these burning bodies anyhow. I decided that I would return to the women bathing in the Ganges, another ritual that seems strange to me but much more cheerful. Besides, there no one was going to dictate our photography.

We wandered the back streets near the funeral ghats for a while looking at the life that ripples out from death, the peripheral activities of cremation; enormous piles of wood gathered for the fires, shrines, shops and street life. Here we were able to rid ourselves of the photo monitors; this was not their territory.

Days 20 and 21

In the days we were in Varanasi, the ghats became our neighborhood; whenever we stepped out of our hotel, we were in the midst of the activity, and turning right or left brought us more.

At one point, we decided to venture into town, to brave the congestion of street life away from the river, in order to visit two temples. We hired two bicycle rickshaws near the corner where we had originally been dropped off. (We had a hotel porter escort us through the warren of streets to the main street). We couldn’t enter one temple or photograph at the other, but the ride was interesting. In the rickshaw we are high enough to get a pretty good view of the bustling street activity.

We spent three nights in Varanasi. We had to make plans to go west to Agra and beyond. Rather than mount the iron horse again (as you are supposed to do if thrown) we decided instead to fly to Delhi and hire a car from there to Agra. All was arranged by Dilip from Rajasthan with whom I finally made contact via my cell phone. The flight left in the afternoon which gave us time to photograph on the way to the airport. We stopped first at a spotless Buddhist shrine featuring colorful prayer flags and a grouping of larger than life statues. Next to a well manicured zoo where we saw giant pelican-like birds. But these were six or seven times the size of pelicans - amazing!). I bought a couple of hand made wooden toys after some frantic negotiating.

On our way, we came upon a long wall of cow pies drying with young women patting them into shape. These are a major source of fuel, transported

to market in baskets. Each one has a hand print, testimony to the intimacy of the human touch in recycling animal waste.

The airport was small and casual, the flight quick and easy.

Days 21 and 22

In Delhi we were met at the airport by a driver and set off immediately for Agra. But the driver (sent from Rajasthan) didn't know Delhi, and he didn't know Agra either. Plus, he was tired from his long drive and almost falling asleep. We stopped a tourist restaurant where we and a young American girl (traveling in the other direction) were the only customers. Lousy food and a tourist rip-off. Trying to find our hotel, we drove around Agra for about 30 minutes, finally picking up a man on the street to guide us. So, we didn't get to sleep until after midnight, another long day. I don't think anyone back home realizes how hard we work when we are photographing; we generally finish exhausted. But somehow the travel is more tiring than the running around and photographing.

The hotel (Pushp Villa) was billed as new, but it had obviously been fitted with a new veneer put over the old structure. Also billed as having a view of the Taj, the large window in our room was so dirty and cracked that I couldn’t see much of anything. Finally, I could make out the Taj in the distance, nestled among factory chimneys. The door jams of every room showed signs of attempted forced entry. But we were here, and here to see the Taj Mahal.

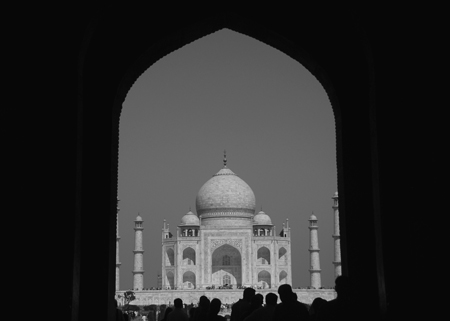

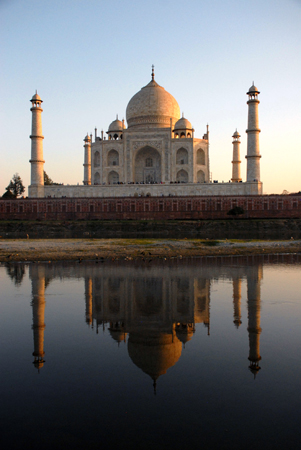

The Taj is truly remarkable and beautiful. Overwhelming. I wasn't sure how to deal with it photographically – the photographic history of it is so intimidating - so I mainly walked around and admired the wonderful architecture. The interior, where all the jeweled inlay is concentrated, is kept very dark, so you could only look at the inlay by flashlight through a metal screen. Not very satisfying photographically or otherwise. It was jam-packed inside, and noisy too, given the acoustics which amplify every sound. I exited quickly and spent my time walking around the outside and to the flanking buildings to the left and right. The scale and proportions are really wonderful.

We also spent a pleasant hour or two at another Mughal tomb, Itimad-ud-Daulah, another mini-Taj, (like the Venice of such and such) not as elaborate, sandstone rather than white marble, but far more accessible. It had a promenade overlooking the river and buildings set around a large open yard. Inside there were a series of small rooms with inlaid tiles still in good shape. We found a series of handprints done with green dye, modern I’m sure, probably done by some of the youths hanging around the river.

We then went back to the Taj to get a boatman to pole us across the Yamuna River to view the Taj at sunset. Sal was keen on it, but I was less than impressed. In fact, I ended up being disgusted by the pollution of the river (full of sewage and industrial waste from factories upriver as far as Delhi). Being out in that crap, looking at India's crown jewel at sunset really put me off.

The authorities are making some gestures toward protecting their greatest monument, but it’s a loosing battle. No gas vehicles are allowed within a mile or so of the entrance of the Taj, so we went by horse cart once and electric rickshaw the second time. But the town of Agra is totally polluted; smokestacks dot the horizon all around the Taj. There are said to be some 1700 factories in Agra, many illegally established without permits or through bribes. The sacred Yamuna is a sewer, carrying waste of all sorts all the way from Delhi. When we asked people about the dirt, they said the Monsoon will wash it away. But the heavy rains come just once a year – and where does it all go? Security is also tight; everything is inspected, and I had to check my calculator before entering. They were also checking kid’s motorized toys. But none of these measures is going to help save the Taj Mahal; the foundations are in danger from the river, and pollution is eroding the fine marble. Cleaning solvents damage it even more.

We found a good restaurant, newly opened, and went there both nights we were in Agra. But I came down with my first case of tourista, so the trip to Rajasthan the following day was pretty miserable. I couldn't eat, had no energy and had the runs. Rather than from the food, I think my squeamishness was due as much as anything to my reaction to viewing the crown jewel of India as the sun slowly set while standing in the filth of the river. In any case, it was my lowest experience in India; instead of reveling in beauty, I was wallowing in shit.

Day 23 & 24

Rajasthan is a totally different part of India. I can understand why it is India's favorite tourist destination. Dry and dusty, but the weather is good - the weather on this whole trip has been unusually good - hot during the day but not too hot, cool at night but not cold. Plus, no humidity. Further, the roads are new and straight and not heavily traveled. The state of Rajasthan has been putting a lot of money into infrastructure, roads, hotels etc. and it's paying off.

We drove from Agra to Jaipur to meet our agent, Dilip, and pay him for the trip, the driver, hotels and air fare back to Delhi. At that point, I was still under the weather, but I found him to be quite a nice guy. He offered lunch in a restaurant downstairs from his office, but I just stretched out in the booth and tried to rest. We had decided we did not want to tour Jaipur, so we didn't try to see the fort or anything else; we just got on our way to Pushkar. Tired of cities, we opted for the small town experience.

The hotel (Master Paradise) in Pushkar was excellent with an inner courtyard and spacious rooms. Recalling the old Peace Corps regimen in Africa for fever, I skipped dinner and went to bed fully clothed plus a sweater and slept for 12 hours until the next morning when I awoke refreshed; I had sweated everything out and was ready to go out exploring.

As soon as we got into town, we ran into a wedding - not the actual wedding but the preliminary tour of the town’s holy shrines by the groom (accompanied by a small boy) on horseback preceded by a brass band a retinue of brightly saried women and a small crowd all proceeding through the streets. We jumped out and followed along. Pushkar turned out to be a pretty and placid town surrounding a spring-fed lake. There are shrines all around the lake with people bathing and worshiping in a 360 degree circle. More relaxed and much smaller than Varanasi, Pushkar offered lots of opportunities to photograph the women. I continue to prefer the mystery and ambiguity of photographs from behind rather than the specificity of individual faces.

All along I had been commenting that I hadn't seen a breast in India - but after hints in Varanasi with the women bathers, in Pushkar I was finally rewarded. The women bathers here were far less self-conscious. I tried not to be too obvious in my appreciation. It's noteworthy that for all the sexuality depicted in the temples and sculptures, painting and bas reliefs, Indian women are quite proper and fastidious - not even a mother nursing - in public. Some years ago Richard Gere shocked the nation by publicly kissing an Indian actress; as a result, he was banned from the country.

It's fun traveling with Salvatore, because he talks to everyone. As a result, he's been blessed, had his feet washed, been anointed, had mantras said and coconuts broken and has been drawn into ceremonies and offerings - all at a cost, of course. The most aggressive hustlers in India are the priests and holy men who want contributions - not for themselves, you understand, but for the gods. As for me, I refuse to take anything or give anything; all that I’ve seen serves only to confirm my belief that all religion is a collection of silly superstitions. A long time ago, as a young man, I vowed never to kneel to any god. And now, if I could, I'd vow never to take my shoes off to any saint, Hindu or Moslem (if they have saints). But that's where they have you; in India you are always being told to leave your shoes. My feet have been hurting the whole trip from the constant need to remove shoes to go where we want to photograph. Obviously, I need to learn more about the religions practiced here if I am going to fully appreciate what I am seeing; without that understanding, I am left to visceral reactions stemming from the religious prejudices I have brought with me. I’m not sure my photographs will be strong enough to open that door.

Sal was here 30 years ago (for six months on $5 a day) so in a way he is re-living his past experiences, in particular the bong lassies, the yoghurt drinks spiked with marijuana. Our driver, Bhagwansing, has also kept him well supplied from the market. As for me, I've been thinking a lot of Africa 40 years ago, comparing and contrasting India to my experiences there, so In that sense, although in India for the first time, I've been re-living my past as well.

Day 25

The next morning we went to Ajmer, only about 15 kilometers away from Pushkar but another world entirely. It’s a Muslim town built around the tomb of a C13 Sufi Moslem saint, Khwaja Muin-ud-din Chishti. Born in Afghanistan, migrated to India, he preached the unity of all religions and therefore tolerance and cooperation between them. His influence is so strong still that he was credited for preventing anti-Islamic violence when other parts of India erupted in religious violence after the destruction of the Ayodha mosque by Hindu fundamentalists in 1992.

We had to leave our car in a garage outside the gates and walk in or take a pedal rickshaw up the crowded main street to the tomb. As we came near, we encountered a hit parade of deformity; every kind of cripple and afflicted come to receive alms in the Moslem tradition. People without legs or limbs, in wheel chairs, on platforms, or just lying in the street formed a gauntlet of desperation. In addition, women roamed the streets begging. Traffic of all sorts in the narrow street jockeyed for passage around the beggars; motor bikes, rickshaws, bicycle rickshaws, donkeys, you name it. Shops lined the street, and vendors milled about selling everything from food and flowers to socks and skull caps.

The guards at the entrance to the tomb were very hospitable and helpful; the image of American-hating Muslims is certainly not true in India. They seem very much Indians first and Muslims second. They showed us where to leave our shoes, passed us through crowds and then the metal detectors and escorted us inside pointing out what was what. Inside the tomb complex (another city within a city) throngs of worshipers crowded in; there were musicians and singers, people being blessed with peacock whisks tapped on their heads , shoving, pushing, chanting, praying. Because of a bombing several months ago, we were not allowed to take in cameras, so we took turns going in. There was constant, intense activity and worship. I saw a man with a small digital camera, and I tried to tell that to the guide without actually pointing out the man, but my guide simply denied the possibility – although he did allow that cell phone cameras would be o.k.

We went back to our hotel in Pushkar - very nice and comfortable - mid day and then went out to photograph the lake and its periphery in afternoon light. We ran into another wedding with another groom on horseback and another band of four or five horns playing (not necessarily together) four or five tunes. At the same time a sound cart blasted music on eight big horns at maximum decibels – ear splitting for anyone nearby. From the veranda of a rooftop restaurant we could look down on a small vegetable market spread out in an intersection. We had cold drinks and hung out watching the sun lower.

Pushkar is a sort of hippie town organized for tourists, so there are all sorts of shops lining most of the streets. We began shopping for cloth but found the shop keepers would not bargain at all; in the end, it was us who came up in order to get what we wanted.

On our way out, we returned to Ajmer the next morning in part to thank the guards at the tomb for their graciousness and in part to get more photographs. Leaving our car at the gate, as we had the day before, we took two pedal rickshaws to the main gate of the shrine and had them wait. We photographed the entrance and all the people milling about. Some of the beggars were o.k. with photographs (for alms) some not. But I didn’t try. People were friendly, as usual, and several asked to have their pictures taken. Those who didn’t ask were nonetheless willing participants.

Day 26, continued

On the way to Bikaner, we passed a shrine that looked to me like a three dimensional comic book – but one which inspired devout worshipers. The entrance was through a larger than life-sized lion’s mouth, and inside the compound was an enormous pink Ganesh. They were still constructing the mountain backdrop. Outside, the lion was flanked by a statue of a giant four-armed figure holding a severed head. I confess I’m baffled at the meaning of all these Disney-like figures. But we witnessed several people come to pray with great seriousness, including a newly married couple. The bride followed the husband, attached by a sash over his right shoulder.

We came into Bikaner but rather than stop at our hotel, we headed south west out of town to Deshnok where the Karni Mata Temple is located. Sal didn’t want to miss it. This is a temple devoted to rats which have free run of the place and which are amply fed milk and food. Once again, the religious or spiritual reasoning behind the worship of rats eludes me. But evidently, the theory is that these rats are all reincarnations – or pre-incarnations also - so these could be your relatives running over your feet. Despite all the food, these were the scrawniest looking rats I’ve ever seen, small and scruffy. I had plenty of opportunity to look closely at several.

I knew beforehand I hadn't much stomach for this, but I went in anyway. I lasted about 5 minutes. We arrived in the afternoon, only to learn that nighttime was the prime time, the time the most rats came out. We decided to work with what we had rather than think about returning – although I know it crossed Sal’s mind. The stench was awful, not to mention walking over rat shit in bare feet. (Actually, we both were smart enough to put on socks). Netting overhead offered the rats some protection from predators but didn’t keep pigeon shit from dropping and mixing with the rat droppings. Together they coated the floor. There were elaborate shrines with offerings of food. People were lying down and letting rats run over them, a special blessing, I guess. One man drank from the same large tray of milk as the rats kneeling right alongside them. People actually live in this temple with the rats. Salvatore asked one woman what she thought of all these rats; "They are our Gods." she said. What nonsense!

I passed the time outside in the shade and more or less a shit-free zone. A man approached to talk and it turned out he was from Vancouver, come home to claim his bride and take her back. He runs a construction company there. The bride turned out to be a lawyer, very pleasant. Talking about her anticipated adjustment to Vancouver, she pointed out that Indian law is virtually the same as British law, but Canadian law is very different. I think he wanted to impress her that he could meet and greet whites. I was dying to ask if this was an arranged marriage, how they met etc. but I held back. Also, why did they come here? Once again, it was a place of serious worship that eluded me.

In Bikaner we also visited two Jain temples (Bhandreshwar and Sandeshwar) built side by side on top of a hill. Both feature a series of historical and devotional murals encircling the inside walls and shutters and elaborate inlay tiles on the ceiling and floors. A resident priest showed us around, posed and then took my picture by placing my camera on the floor and having me lean over so that the domed ceiling formed a backdrop.

From the temple tower, I caught a glimpse of bright cloth being hung out to dry on rooftops, so after exiting, we walked down the street a bit to have a look. We entered a Moslem neighborhood filled with dye vats and washing tanks run mostly by children. At one point, a young girl went up on the roof of her house to spread out the dyed cloth. Against the sunlight, she created a ballet of veils, and I stayed for quite a while photographing her.

In Bikaner we stayed at Hotel Sagar, with a large open courtyard where we ate and watched the other tourists ascend and descend the outdoor steps. I guess that’s what photographers do in their spare time.

Day 27

The main attraction in Bikaner is a very large fort built in the sixteenth century now filled with artifacts donated by descendents of the Maharaja including old photographs, furniture and exhibits – and a WW1 era airplane.This is the first Rajasthani fort we’ve seen, having passed up the more famous one in Jaipur. The architecture features elaborately tiled rooms and delicate filigree screens made of sandstone. The walls, too, are often decorated with painstakingly carved bas reliefs.

We had to go in with an Indian tour group, but the guide gave his spiel in English for us and was very accommodating. He had a sense of humor, too, but all the historical details sailed past me. As always, I’m looking for what I can photograph that’s not so obvious, not on the ‘official’ tour.

On the way out of town we passed a busy commercial section of town with camels pulling more than their weight and trucks with such enormous loads (of cotton) that I couldn’t resist stopping to photograph them. (It’s still a shock to me, with my romantic vision of camels strung out in elegant desert caravans, to see them as prosaic beasts of burden.)

Then we came across another of the ubiquitous shrines along the road that are often so unusual. This one was in the form of a large abstract cat and was attended by a priest clad head to toe (ankle) in pink. Goats were running free all around the shrine; evidently they were regularly sacrificed there. We decided we hadn’t the time to take in a sacrifice, so we took pictures and went on our way. On the way out, kids crowded around the car, egged on by Salvatore, all shouting excitedly. To them, we were as exotic as the shrine was to us.

Day 28 & 29

From Bikaner we headed West to Jodphur where we were to stay for three nights. On a gamble, I gave up the idea of going to Delhi before my flight home and opted to stay an extra two nights in Jodphur instead. I put all my eggs in the Jodphur basket - but in the end, the basket didn't hold. Jodphur is the largest city in Rajasthan, another bustling dusty dirty chaotic city. Our hotel, Haveli Inn Pal, was right in the middle of it all, next to the market. And I eventually decided Jodphur was not where I wanted to spend five days at the end of the trip.

Jodphur is the famous blue city that I've long had a fascination about. I was looking forward to seeing this as a highlight of the trip. And, indeed the city is blue, but from above; at the street level, it does not have the blue cast that is so striking in the photographs I had seen. It wasn’t until we went up to the fort and looked down on the city below that the blueness became prominent. The blue is mostly on the upper stories of the houses.

The fort sits on a high hill and atop enormous walls. We found an agreeable motor-rickshaw driver outside the hotel, so we used him for all our trips around town. The first evening, after a brief look at local cloth dyeing, we went up to the fort just to see the outside and look at the town from above. This was when the blue cast was first revealed.

The next morning we went back to the fort. We spent most of the morning walking around inside and photographing. It really is enormous, full of rooms and passageways and balconies. I opted for the audio guide which was very well done and took about two hours. I didn’t see everything, but what I did see was well described. This fort, like the one in Bikaner, features handprints of the “satis” - women who chose to die for their husbands killed in battle. This seems to be a common theme throughout Rajasthan, part of the warrior mythology. With all the wars and repeated conquests of these forts, women must of had plenty of opportunities to perform sati.

Afterward, I did some shopping at the official gift store where the prices were fixed (and high) but the quality and variety and display of crafts was better than what I could see in the shops or market.

After touring the fort, we walked down into town in order to photograph on the streets. In my image of Jodhpur, I was hoping for bright saris against the blue walls. Our rickshaw driver walked along with us. He led us around some of the neighborhoods, so we got a pretty good sense of the town. At one point we came upon a group of kids all with hennaed hands. They followed us up and down the streets as we photographed.

Going out at night seemed excessive, so mostly we stayed in the hotel. There is an upscale hotel adjacent to ours sharing the same courtyard entrance, and we found its rooftop restaurant more congenial than ours, so we went there for dinner. We could look over the market and the streets below, and after rigorous days shooting, that seemed close enough for us at night. At this point, I was unable to eat any Indian food - so I survived on big breakfasts and Indian renderings of pasta.

Salvatore was scheduled to return home on Friday (day 30) so we said goodbye; he took a taxi to the Jodhpur airport, and I hired a car to take me further west to Jaisalmer in an effort to escape city life.

Day 30 & 31

The ride from Jodhpur to Jaisalmer was as straight as an arrow with little traffic except for several convoys of Indian military trucks. This area is near Pakistan and is evidently a major training ground; we (the driver and I) passed scores of military camps, mostly tents in fields with dozens of vehicles. The landscape is flat and sandy.

The hotel that had been booked for me was outside of town in the midst of new construction, all dusty and brown. It (Dhola Maru) was named I learned later for a romantic child bride and groom. I was the only guest. After checking in, I asked the driver (whose English was limited to yes and a few nods) to take me to look for Sawar, my friend Marilyn’s friend. She had worked here with him on some art project, so I decided that I should follow her advice. (It’s a principle of mine in traveling to follow every lead given by a friend.) The driver went to search him out while I waited in the car; Sawar wasn’t available but would be tomorrow. So, I went into town to see what I could find. (The main town is pedestrian only, so the driver had to wait for me in the car park.) Since my hotel had no internet yet, I set out to find an internet site and located one at the top of a flight of dark stairs. I spent about 20 or 30 minutes writing an e-mail and headed to the fort. On the map, it looked to be quite a distance, but Jaisalmer turned out to be very small and easy to navigate. I passed a few recommended restaurants and marked them for my return. Soon, I was picked up by a young tout who I allowed to lead me through back streets to various shops (since I knew this was my last chance to shop) where I looked but didn’t find the elephant pillows I wanted. At one point, someone on the street told him I had been looking for Sawar earlier. He knew him. Finally, convinced I wasn’t going to buy, he released me near the fort.

This fort is different from the others in Rajasthan in that people live within its walls; it’s really more like an Italian hill town. I decided to eat rather than go into the fort at night – it doesn’t close. Rather than return to the restaurants that had been recommended, I decided to try a restaurant right inside the fort – ‘Little Italy’ (I kid you not) – run by young Nepalese. I went up to the terrace and had a beer, then penne pasta with garlic and onions. Just what I needed! Afterward, wandered into the shop below and found the pillows I wanted.

The next day after breakfast, I returned to the fort. The first thing I came upon was a little girl on a high wire doing the same tricks over and over again, expressionless like a trained monkey closely watched by her father who collected the money. I wondered what kind of life this girl had; doing the same routine without variation every day for hours. Serfdom. I accepted the proposition of a guide, a young student, and went with him into the fort / town. Fifteen buses of Jain pilgrims had just arrived, so the place was full of people all dressed in white. This was the first time I had seen Indian tourists behaving like Chinese tourists, traveling in groups. They were having a good time. When the crowd dissipated, I went into the elaborately carved temple. Then, I went around the town and up to the ramparts to get a view. My guide said there was a really good haveli in town worth seeing, so I accompanied him out of the fort into town to see what turned out to be three or four havelis side by side. One was open to tourists. We climbed up four flights past floors of empty rooms to the roof. Later I returned on my own and wandering around I was able to photograph street scenes including a group of women holding some kind of meeting.

After a rest at the hotel, I went back to see Sawar and found his office / studio / art center. Folk Arts Rajasthan is a place where lower caste women come to learn to do art and use recycled materials. While we waited for Sawar to appear, I looked around at the displays and samples; meanwhile the driver was being harangued by a turbaned man. Given the driver’s totally mute and expressionless reaction, I gathered he was not in sympathy.

Sawar had been described by Marilyn and in town as the blue-eyed musician, and indeed he did have dark blue eyes. He explained that he was the 37th descendent of musicians in his family and showed me a picture of one of his forbears playing for the Maharaja. “We were treated as slaves then,” he declared, “And we still are.” He went on to explain something of the caste system. His family were musicians, lower caste. He still could not drink tea in the marketplace. (I had read that in some places, separate cups are kept for lower caste customers). I asked him how people could tell what caste a person was. They ask, he said, just as they ask you what country you’re from. And if you lie to them, you can be beaten, even murdered.

So his center was for lower caste women, to bring them together, train them to make artifacts (from recycled materials) and give them education. In Jaisalmer, out of 8000 lower caste children, only four are in school (including one of Sawar’s daughters). There is still no right to education for lower caste children, and the only reason there are these four is that foreigners have paid their tuition to a private (Catholic) school.

Sawar was soon on his way to the USA to do a two month tour of the East coast from Washington to Maine. “It will be cold,” I warned. He said he knew; he had been to 37 countries. (His situation reminded me of Cuba where it is the artists, who can travel and get access to U.S. Dollars are doing reasonably well, better than more traditionally higher status professions.)

I wish I had had this discussion earlier in the trip. But I decided to begin asking people what caste they were. The first person I asked was a vendor in the market. He pointed to his earring and said that meant he was Rajput. But within that he must have had another caste (like Sawar the musician) because he went on to tell me that people in the market called him by his class – not his real name. “My name is Valentin; if you ask anyone for that name, they won’t know who you’re talking about. They just shout my caste name.”

Dinner was at Little Italy again – same menu; pasta is all I can take. On the way out, I ran into the tout of yesterday who told me “you bought from that shop but not from me.” They seem to know everything in this small town. I spent the last night repacking everything for the flight home, always a subdued task.